Most of the time, we use analytical techniques to get inside the head of the composer. Looking at a piece of music, or listening to it, why is it that way? What can we learn about improvisation using our analytical techniques? For this week's technique, we will be analyzing a piece of music for the purpose of improvisation. The improviser is at once the performer and the composer. But that doesn't mean that the improviser just plays whatever. Analyzing the chord structure of a tune can inform the improviser to choose the notes to play that will best complement the song. Improvisation has rules. You heard me. Rules. If you are up to improvise on a tune with a jazz band, you have to play in the same key they do. [or you will sound like Charles Ives] You have to use the same meter. You have to use the same style. [You can't change to a march or mariachi if the band is playing bebop.] If you want to sound good, you have to be aware of the chord changes and be intentional on the notes you choose. Well, you can break any of these rules you like, but if you do, you will at best sound like an amateur and at worst, just plain lousy. There is an exception - sort of - it's called Free Jazz. They say it has no rules. Well, I say that the rule is that you can't use all the rules. Would it still be free jazz if I started playing a tune in strict meter with a traditional melodic line and harmonic progression?

Look up the tune below

on YouTube, listen to a bit of it and see what you think: Free Jazz (Ornette Coleman)

Well, that's not the type of improvisation we are going to study.

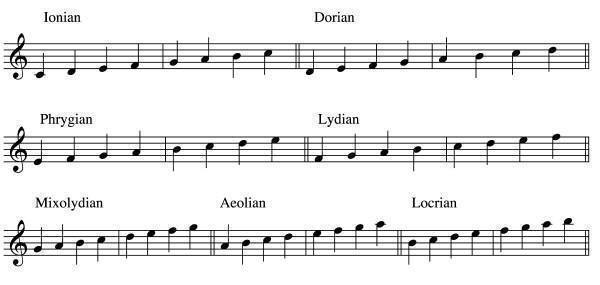

IMPROVISATION PART 1 Do you remember studying modes?? Understanding the mode scales is a great tool for the improviser. The experts can take this process to quite sophisticated ends, but we are just going to dip our toes into the water of using modes for improvisation. For those of you who do improvise or who teach it, you will know that there is much more to learn. I teach my music theory students to remember the modes this way | I DON'T PARTICULARLY LIKE MODES A LOT |

|

Ionian Dorian Phrygian Lydian Mixolydian Aeolian Locrian If you remember your music theory, the pattern of each scale is most concretely (is that a word?) illustrated by beginning on a different white key on the piano. This creates 7 different scale patterns - the half steps and whole steps are in different places. Ionian: C to C Dorian: D to D Phrygian: E to E Lydian: F to F Mixolydian: G to G Aeolian: A to A Locrian: B to B

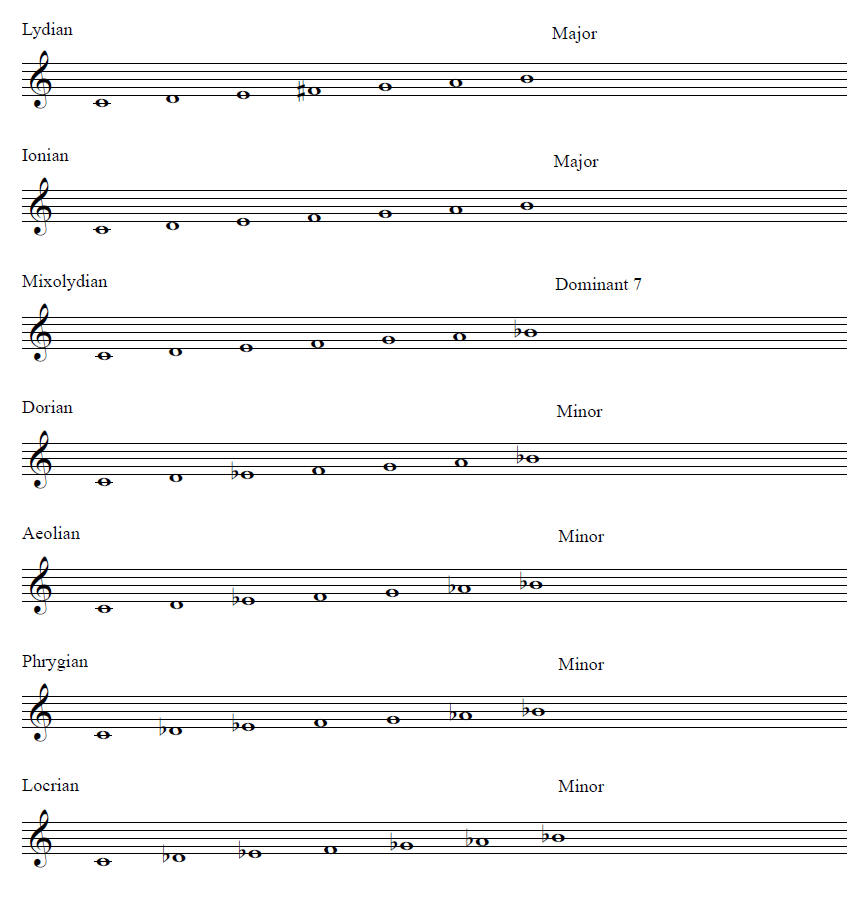

If you started each mode on the same note, the pattern of half steps and whole steps would look like the example below. Each of the scales below is also labeled as "Major" or "Minor" and one is designated "Dominant 7." The major sounding scales are those that have a major third interval from tonic to the third. The minor sounding scales have a minor triad interval from tonic to the third. The Mixolydian scale has a major third and a minor 7th (like a dominant 7th chord).

Note: if you need additional review of the modes, check your favorite theory textbook, or the Help page. You may have also learned this: Ionian is the same as a major scale. Dorian sounds minor with a raised 6th scale degree. Phrygian sounds minor with a lowered 2nd scale degree. Lydian sounds major with a raised 4th scale degree. Mixolydian sounds major with a lowered 7th scale degree. Aeolian is the same as natural minor. Locrian sounds minor with a lowered 2nd and a lowered 5th. Now let's add 3 more scales that improvisers also use. All 3 of these below are used for dominant chords. (There are others, but these are the top 10!)

These add some really interesting patterns! The first is a Lydian scale with a flat 7th scale degree. The third one is a Diminished scale. You may remember this one from theory: 1/2 step, whole step, 1/2 step, whole step, 1/2 step, whole step, 1/2 step The Altered scale above is like the diminished scale for the first 5 notes, then is different.

OK - now how to apply this information to improvisation: When you are improvising, you will often have a lead sheet symbol to read.

If you need a quick tutorial on how to read lead sheet symbols,

there are many on YouTube, so pick your own level and

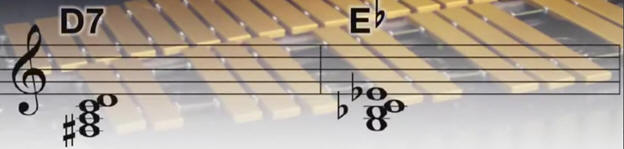

review! When reading a lead sheet symbol, in order to improvise, you might play the chord itself (if you are playing a harmonic instrument like a piano or guitar). But, you will also improvise melodically. You can use the scales above to decide what notes will fit with the given chord. The scales can be divided into those that work with major sounding chords, minor sounding chords, and dominant chords (Mm7 chords) Major: Ionian, Lydian Minor: Dorian, Phrygian, Aeolian, Locrian Dominant: Mixolydian, Lydian flat7, Altered, Symmetrical Diminished For example, you may see Gm7(b5). That chord would be spelled

This chord would sound minor with a flat 5. What scale would you choose to improvise on while that chord was sounding? The minor sounding scale with a lowered 5th scale degree is the Locrian scale. So, improvising on a G Locrian scale would complement that chord.

IMPROVISATION PART 2: Guide tones, guide lines, common scales, constant structure By the way, random 'noodling' is not improvisation. I call that exploration. ("I wonder what this will sound like?" - noodle, noodle . . .) True improvisation is knowing what the music will sound like before you (or anyone else) hears it. That begins with informed decisions based upon the synthesis of your musical knowledge and musicianship. Guide Tones Another element to consider in choosing improvisational material is that some chords need to resolve. Dominant sounding chords have tendency notes that move in a certain direction. For example, a G7 chord wants to go to a C chord because the F tends to resolve the half-step down to E and the B resolves by half-step up to C.

So, the improviser should choose one of those notes at the point of change from one chord to another.  This is not a precise process. Other factors contribute to those decisions; for example, if there is an implied melody in the song or what chord came before. However, it is a tool that the improviser can use to make informed decisions in choosing melodic lines. This is not a precise process. Other factors contribute to those decisions; for example, if there is an implied melody in the song or what chord came before. However, it is a tool that the improviser can use to make informed decisions in choosing melodic lines.

These notes that you can identify that need to move by step in order to resolve are called guide tones. When improvising, if you detect that the resolution is going up, the improv line might go up as well to emphasize it.

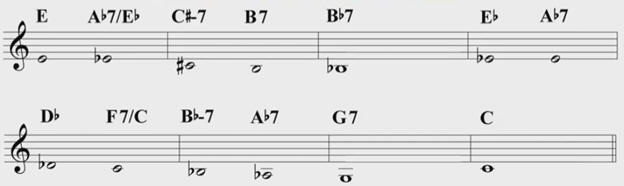

Guide Lines A series of guide tones in a row is called a guide line. Sometimes the guide line will be given to you in a lead sheet. In the example below, there is a nifty guide line indicated by the bass line notes (tones under the slash)

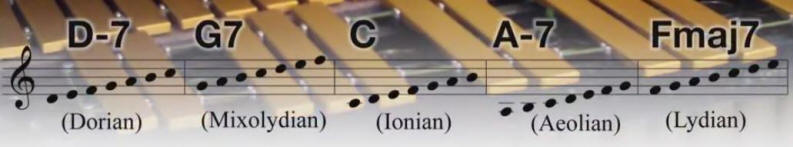

When improvising, the soloist can keep an eye on the guide tones and follow those. Especially if the chords change quickly, this can be a handy analytical tool to follow! Common Scale If several chords in a row use the same scale, you can group them. Each measure below could use a different scale, but what they all have in common is the same diatonic scale (no sharps or flats). This could allow the performer to improvise across all 5 measures using the same palette of notes.

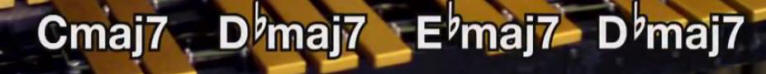

Group them together into a larger unit so that longer phrases can be played, more melodic. Constant Structure The type of chord stays the same. For example:

Any melodic phrase played on one chord can be just transposed onto any other. This is great for repeated/sequential material. A common form of constant structure occurs when chords move chromatically. Chromaticism is the improviser's best friend – add chromatics to be able to land on the right beat with the correct note.

Created and maintained by Vicky V. Johnson |